Aerodynamics

This section covers the fundamental principles of aerodynamics, including the four forces acting on an airplane, the concepts of lift, weight, thrust, drag, and how they influence flight performance and control.

The Four Forces of Flight:

Lift:

- Opposes the downward force of gravity.

- Produced by the dynamics of air acting on the wing.

Weight:

- The total load of the airplane.

- Pulls the airplane downward due to gravity.

- Opposes lift.

Thrust:

- The forward force produced by the engine and propeller.

- Propels the airplane through the air.

Drag:

- The rearward force that opposes thrust.

- Two types of drag:

- Induced Drag:

- Result of the wing creating lift.

- Caused by pressure differences between the upper and lower wing surfaces.

- Creates vortices, strongest at the wing tips.

- Impossible to eliminate but can be reduced with design features like winglets.

- Parasite Drag:

- Caused by the airplane's fuselage and protrusions disrupting airflow.

- Increases with airspeed.

- Induced Drag:

Balance of Forces:

- In steady, level flight:

- Opposite forces are equal and cancel each other out.

- Lift equals weight; thrust equals drag.

- In climbs or descents:

- Forces can be broken into horizontal and vertical components.

- Upward forces must equal downward forces; forward forces must equal rearward forces.

- Weight always acts downward, consisting of vertical components.

- In accelerated flight:

- If airspeed is decreasing, rearward forces exceed forward forces.

- If climb rate is increasing, upward forces exceed downward forces.

Relative Wind and Angle of Attack:

- Relative Wind:

- The airflow experienced by the wing due to its motion through the air.

- Always moves opposite to the flight path of the airplane.

- Angle of Attack (AoA):

- The angle between the wing's chord line and the relative wind.

- Controls airspeed, lift, and drag.

- Not the same as the airplane's pitch attitude.

- Managing AoA is crucial for flight control.

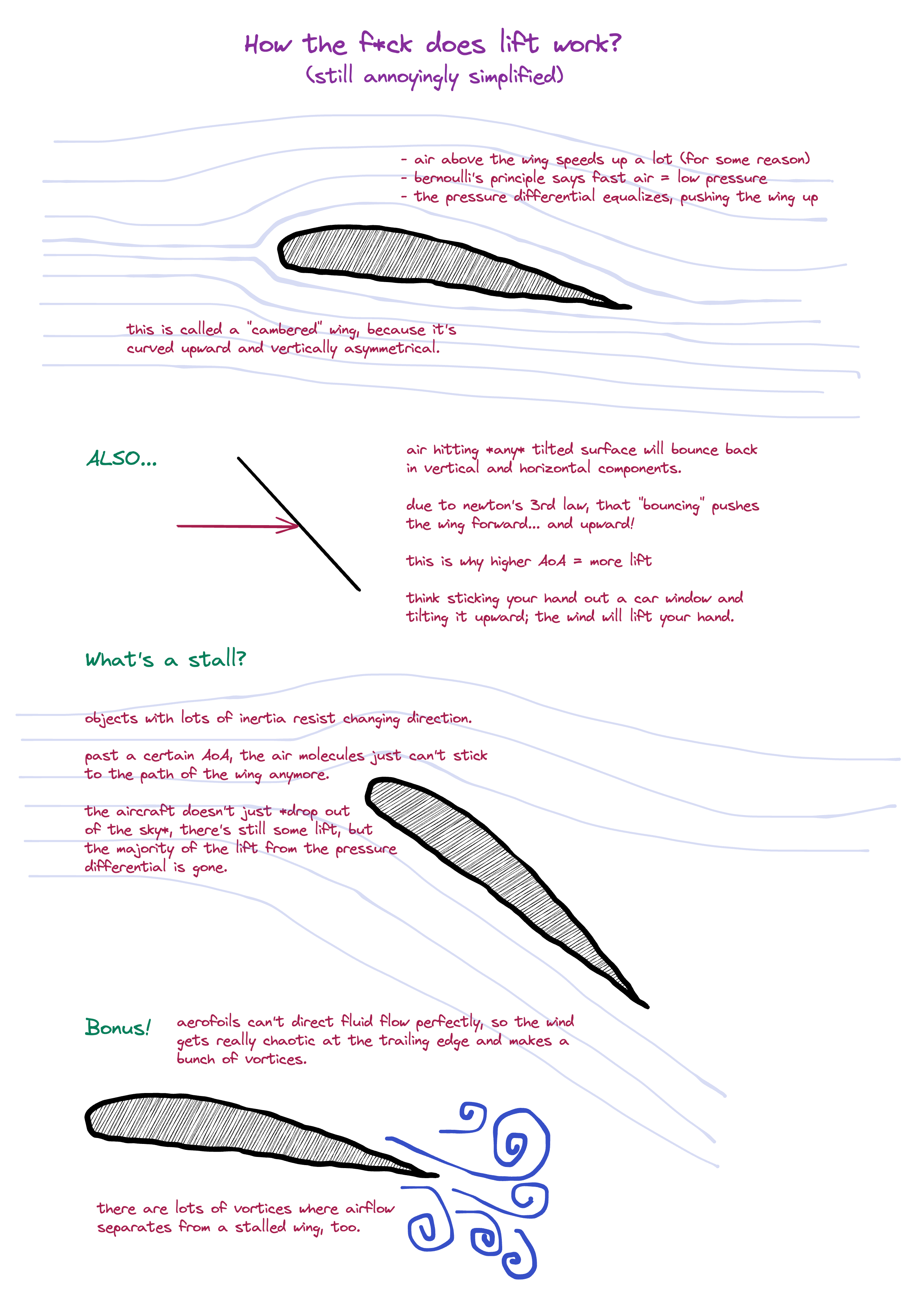

Lift Production:

- Caused by pressure differences around the wing:

- Decreased pressure above the wing.

- Increased pressure below the wing.

- Acts at right angles to the relative wind and the wing's lateral axis.

- At low AoA:

- Most lift is from decreased pressure above the wing.

- As AoA increases:

- Lift from increased pressure below the wing also increases.

- Total lift increases until reaching the critical AoA.

Stall and Critical Angle of Attack:

- Critical AoA:

- The angle at which airflow separates from the wing's upper surface.

- Also known as stalling angle or burble point.

- Stall occurs when:

- AoA becomes so large that airflow cannot follow the wing's contour.

- Lift diminishes rapidly, though the wing still produces some lift.

- Recognizing stalls:

- Loss of lift and control effectiveness.

- Important to manage AoA to prevent stalls.

Wingtip Vortices and Induced Drag:

- Wingtip Vortices:

- Result from pressure differences at the wing tips.

- High-pressure air below the wing spills over to low-pressure area above.

- Creates swirling air patterns that trail behind the wing.

- Induced Drag:

- Caused by wingtip vortices and downwash effects.

- Increases with lift and AoA.

- Design features like winglets help reduce induced drag.

Airflow Demonstration with Tufts:

- Using tufts of yarn on the wing to visualize airflow patterns.

- Observations:

- At higher speeds, tufts streamline with airflow, indicating smooth flow.

- At lower speeds and higher AoA, tufts show airflow separation near the wing root.

- Wingtip vortices become more intense at high lift conditions.

- Center of Lift:

- Point where total lift is considered to act.

- Moves forward as AoA increases.

Stall Characteristics and Wing Design:

- Stall progression from wing root to wing tip is desirable.

- Maintains aileron effectiveness during stall.

- Design techniques to achieve this:

- Wing planform shapes (rectangular, tapered).

- Angle of incidence variation along the wing span.

- Washout: twisting the wing to have lower AoA at tips.

- Stall strips on leading edges to initiate stall at wing roots.

- Purpose:

- Provide ample warning of impending stall.

- Enhance lateral control at high AoA.

Left-Turning Tendencies in Propeller Aircraft:

- Caused by four main factors:

- Torque Effect:

- Engine and propeller rotate clockwise (from pilot's view).

- Airplane tends to roll counterclockwise due to Newton's Third Law.

- Spiraling Slipstream:

- Propeller creates a corkscrew slipstream around fuselage.

- Strikes vertical stabilizer on left side, yawing the nose left.

- Gyroscopic Precession:

- Propeller acts like a gyroscope.

- Applied force is felt 90 degrees ahead in the direction of rotation.

- More pronounced in tailwheel aircraft during takeoff.

- P-Factor (Asymmetric Propeller Loading):

- At high AoA, descending blade on right has higher AoA than ascending blade.

- Produces more thrust on right side, causing yaw to the left.

- Torque Effect:

- Correction Methods:

- Aircraft design features to counteract left-turning tendencies at cruise.

- Pilot inputs using rudder to maintain coordinated flight.

- Importance for Pilots:

- Understanding these tendencies aids in proper aircraft control.

- Essential during high power and low airspeed conditions like takeoff.

Importance of Understanding Aerodynamics:

- Practical Applications:

- Enhanced safety through better aircraft control.

- Ability to anticipate and correct for aerodynamic effects.

- Flight Efficiency:

- Optimizing performance by managing lift, drag, and AoA.

- Reducing fuel consumption and wear on the aircraft.

- Advance to Complex Aircraft:

- Foundation for understanding advanced aerodynamic concepts.

- Preparation for handling high-performance aircraft.

Understanding the principles of aerodynamics is crucial for safe and efficient flying. By mastering these concepts, you can effectively control your aircraft and anticipate how it will respond in various flight conditions.